Once you manage to pronounce “Shakhrisabz”—mastering the sharp, throaty ‘kh’ at its center—the name seems to grow more enchanting every time it’s spoken, carrying a charm that matches the city itself.

The name, rooted in Persian, translates to “lush” or “rich with greenery,” a fitting description for a city of about 100,000 people nestled in the Kashkadarya region of Uzbekistan. It sits roughly 88 kilometers (55 miles) south of the famed Silk Road hub, Samarkand, a frequent base for travelers exploring the country’s historic corridor.

This city holds special importance in Central Asian history. Amir Timur, known in many parts of the world as Tamerlane, was born near the outskirts of present-day Shakhrisabz in 1336. Revered as Uzbekistan’s most influential historic leader, Timur built an empire through power and strategy, becoming a defining figure in the region’s identity.

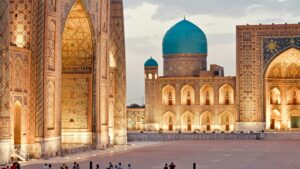

Timur’s reign (1370–1405) sparked a golden era for a distinct architectural movement now called “Timurid,” recognized for grand proportions and striking decorative mosaics. The intricate blue-and-gold tiled madrasas and mosques across Uzbekistan, admired globally today, trace their roots to this period. Some of the most notable surviving examples stand in Shakhrisabz’s historic heart, a district protected under UNESCO’s World Heritage list for its cultural value and monumental craftsmanship.

The Takhta Karacha Pass: A Road Through Time and Terrain

Reaching Shakhrisabz from Samarkand requires a drive across the Takhta Karacha Pass, also referred to locally as Kitob or Aman-Kutan. The mountain road twists sharply as it climbs to an altitude of 1,650 meters (5,400 feet), framed by the often snow-dusted peaks of the Zarafshan range.

The route threads through vineyards, cotton farmland, and roadside bazaars that remain a living tradition of the Silk Road spirit. Because of the road’s steep curves, buses and heavy cargo vehicles are not permitted to travel this pass, keeping traffic to smaller, more agile transport.

Along the way, travelers commonly sample or purchase kurt—dense, dried cheese spheres made from fermented milk, once favored by caravan traders for their durability on long journeys. For those less accustomed to the strong flavor, stalls also display dried figs, nuts, and fruit, offering a milder introduction to local snacking culture.

Descending from the high point of the pass, restaurants dot the roadside, delivering open-air views of the green basin below. Lunch often features shashlik, the region’s signature grilled meat skewers, cooked over charcoal and served with simple seasoning, reflecting Central Asian culinary staples.

Monuments, Ruins, and Restored Grandeur

Several tourism companies, including GetYourGuide, promote organized day trips from Samarkand to Shakhrisabz, highlighting the city’s compact but layered concentration of historic sites.

Among the most discussed stops is the Ak-Saray Palace, once Timur’s most ambitious architectural project. Construction is said to have taken 24 years. Today, only two large, weatherworn walls of its entrance remain, but even this partial ruin conveys an unusual drama—an aesthetic contrast to many other meticulously restored monuments in Uzbekistan that often appear nearly new.

A statue of Timur now stands in the park nearby, one of three national monuments built to honor him after Uzbekistan became independent in 1991. Each statue reflects a different chapter of his legacy—depicting him upright in his homeland, on horseback in Tashkent, and seated in Samarkand, his imperial capital.

Close to the park sits Kok-Gumbaz Mosque, the city’s traditional Friday prayer site, shaded by mature maple trees. Behind the mosque lies a small necropolis containing a modest tomb originally intended for Timur, though he was ultimately buried in the much larger Gur-e-Amir mausoleum in Samarkand instead.

Across the park, the Dorut Tilovat complex features turquoise domes, a madrasa, and resting sites including that of Shamsiddin Kulal, one of Timur’s respected teachers. The restrained design of these graves, though visually simple, creates a memorable contrast to Uzbekistan’s generally ornate religious architecture.

A former caravanserai nearby now serves as an events hall and restaurant, continuing part of its historic role as a meeting point for travelers and exchange of goods, stories, and culture.

Handicraft shops line the park’s edge, where local artisans quilt traditional garments and embroidered cushion covers. The Art Gallery of Aziz Akhmedov, another frequent stop, blends modern and traditional art with a café offering strong coffee—an unexpected but welcome find in a land more associated with tea culture.